Postdoc Geneva Hutchinson uses art as an entry point to conversations about justice

May 30, 2024

One thing to know about Geneva Hutchinson is that she’s willing to talk about anything.

“I have zero filter, I have no secrets ever, I’m such an open book,” she said with a laugh.

As an artist, she puts those traits to good use.

“I think it is a gift to not be closed off, so I really do try to utilize that as an artist who is open and willing to talk about things that people find uncomfortable,” she said.

Hutchinson, a postdoctoral research associate at the Institute for Social Concerns, creates art that draws attention to the abuse of power toward women. She looks to conceptual frameworks provided by trauma theorists to understand responses to spiritual and physical abuse, and the process of healing from sexual trauma.

The arts are an important mode of work at the Institute for Social Concerns because they provide a concrete encounter with people and communities marginalized by injustice and help people imagine a more just world.

Hutchinson said art has the capacity to open people up to discussions that they might not be willing to have otherwise, especially when the topic is complicated or taboo. She draws inspiration from feminist artists of the 1970s — Suzanne Lacy, Judy Chicago, Miriam Schapiro — who brought attention to issues like sexual assault in an era when such abuses were being ignored.

“I’m happy to make art so that people who may have a harder time talking about things have a space for refuge or conversation if they want that,” Hutchinson said. “And, hopefully, eventually that will lead to deeper healing.”

Her work takes many forms, often mixing the traditional aesthetics of textiles with the modern polish of photography. She uses found fabrics and discarded objects as a way to reclaim memories from past owners, and embroidery as an homage to past generations of women.

The #MeToo movement, which swept across social media during her undergrad years at Clemson, was the spark that helped Hutchinson find her purpose in the art world. The movement prompted women around the world to reveal their stories about sexual abuse and sexual harassment.

“I got really inspired by the women who were sharing their stories, and then was inspired to share my own story,” said Hutchinson, herself a survivor of sexual assault. “I felt that I could use art not only as a means of communicating, but also as a healing process.”

For one of her installations, she put up a clothesline in Trustee Park in the heart of Clemson’s campus and along it hung 10 bras that she had bought from thrift stores. Each bra was embroidered with a quote that women had shared with Hutchinson about their sexual assaults.

“What were you wearing?”

“I told him no.”

“I’m sorry mom.”

The installation went viral on social media and attracted coverage from the Associated Press and other news outlets.

Hutchinson set her sights on MFA programs and came to Notre Dame, where her work and research gained more nuance. She started to explore women’s experiences in Christian “purity culture” and examined the influence of her own upbringing in the South as the daughter of a pastor.

Around the time she was starting her thesis in the spring of 2022, the Southern Baptist Church released a list of pastors and church staff who had been accused of sexual abuse. The list identified more than 700 individuals from cases between 2000 and 2019.

She combed through the list of names and investigated websites and social media to find photos, videos, and audio recordings of the alleged abusers. She read the heartbreaking stories of those who had been abused.

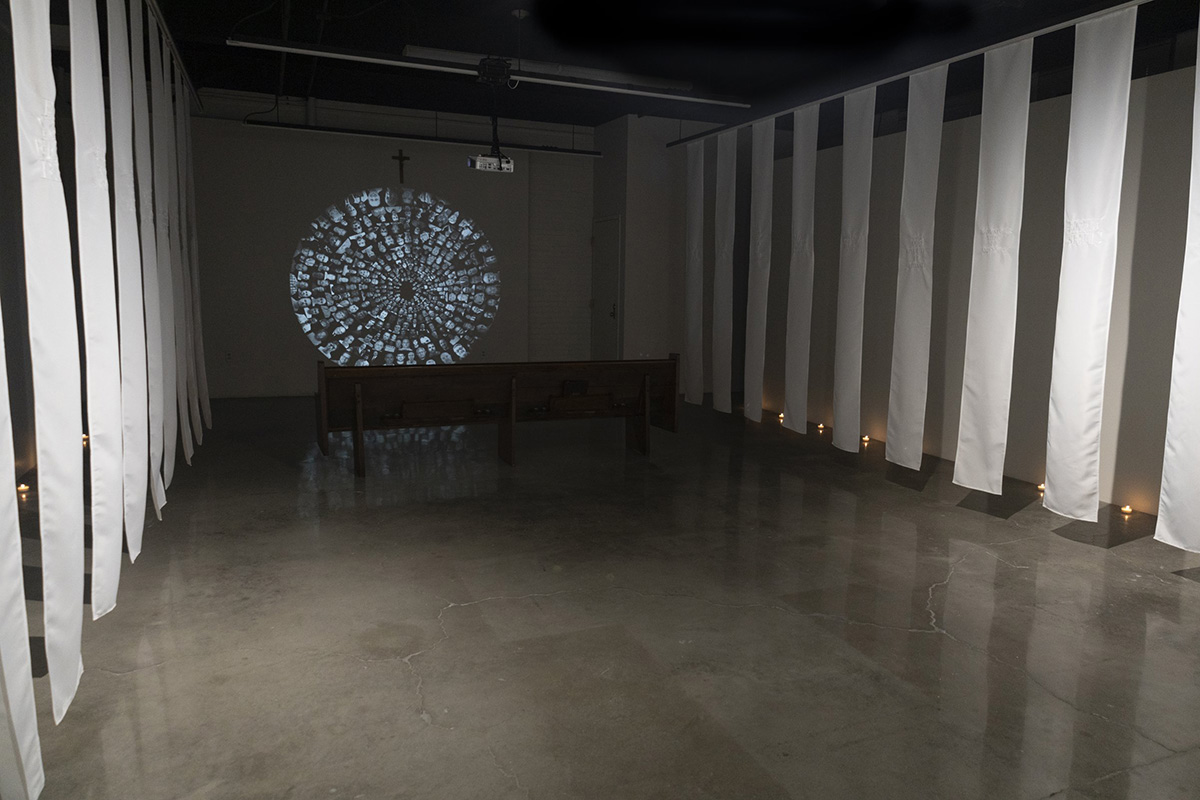

The resulting installation, “God’s Ordained,” was laid out like a church. A circular photo collage with images of more than 300 of the abusers was projected on the wall in the front of the space, suggestive of a stained-glass window. Along the sides, she draped columns of white fabric with embroidered phrases from the victims’ stories, which she referred to as “silent screams.” An audio track of spiritual music interrupted by one of the accused pastors’ angry sermons played in the space.

“My thesis turned into this larger institutional critique. It’s meant to be jarring, honestly. It’s meant to be horrifying because abuse is a horrifying concept,” Hutchinson said.

Her approach to addressing trauma in her work is informed by the research of scholars like Judith Herman, a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. “Work that’s talking about anything traumatic has to be done so intentionally and with sensitivity. That’s something I think about constantly,” Hutchinson said.

She said her involvement with the Institute for Social Concerns, first as a Graduate Justice Fellow when she was an MFA student and now as a postdoctoral fellow, has been beneficial because the Center takes an interdisciplinary approach to justice education and research.

“The Center has been awesome because it’s given me a space with faculty and other graduate students and postdocs who are in totally different areas,” she said. “I get to talk with them about what I’m working on and researching, and affirm that it makes sense.”

She has also appreciated being able to assist with Center courses like Art and Social Change, which combines justice research with the art-making process. That work includes partnering with the Boys & Girls Clubs of St. Joseph County, where students have helped create murals at Foundry Field to showcase baseball stories from South Bend’s marginalized communities.

“Public art can be this accessible entry point into harder conversations,” she said. “Maybe it’s beautiful and then you recognize what it’s about. Maybe it’s visually interesting and compelling and draws you in, but then it also brings attention and awareness to create conversations.”

See more of Geneva Hutchinson’s work at genevalark.com.

Related Stories

-

Biennial Catholic Social Tradition Conference to take up Vatican II’s invitation to discern the signs of the times

-

McNeills in Montgomery—Fellows have transformative experience at Equal Justice Initiative

-

From Ukraine with love—Father Yuriy Shchurko joins the institute as visiting professor of the practice

-

ReSearching for the Common Good: Charlie Desnoyers

-

Collaborating for the Common Good—Institute for Social Concerns hosts interdisciplinary Crime & Justice Working Group