A reflection inspired by the Mozaik Philanthropy WOMAN. LIFE. FREEDOM. virtual exhibition

Visit the exhibit at mozaikphilanthropy.org/woman-life-freedom

I vividly remember the streets of Iran, woven with threads of beautiful traditions and burdened by the iron grip of the government. Streets hold memories that are entwined into the fabric of my being, sweet and bitter. They bear witness not only to my footsteps, but to my dreams, desires, and yearning for a life that always seemed just beyond my grasp.

As a child, I navigated my hometown streets in joy, which soon turned into silence—a silent observer of a world that insisted on dictating my worth and defining my role under the norm of religion. Scrolls of rules from centuries past—written by men—that dictated my gender, clothing choices, and societal role, robbed me of the freedom to sing loudly, to dance in public, and to feel the wind in my hair.

The weight of the mandatory hijab draped over me, suffocating my hair, my body, and my spirit. With each passing day, my yearning to walk those very streets unrestricted and liberated intensified. I craved the gentle touch of the wind in my hair and the warm embrace of the sun on my uncovered skin, free from the chains of judgment and disapproval from my beloved family and society.

In seeking those simple joys of life, I longed to be a boy, to inherit the privileges and liberties that were bestowed upon them so effortlessly. I yearned to sing unabashedly with a voice that echoed through the streets, to express my opinions without hesitation, and simply to exist as myself, untouched by the heavy hand of government oppression and the family traditions that were not sweet anymore. Every single morning of my life when I had to wear a hijab, and every single time that I was arrested by morality police for wearing an “improper” hijab, forged me into a resilient teenager filled with a rebellious spirit.

My last memories of Iran form a vivid canvas in my mind, with hues of hope and determination. A protest in front of Tehran University. Heart pounding in my chest, I stood among other, mostly student, protesters, vulnerable in front of row upon row of riot guards. An hour later, I found myself running with women and men alike, seeking refuge from the advancing riot guards. Beside me were women with hijabs, defying the stereotypes and joining the chorus of voices. In that moment, I witnessed the unity, the voices coming together demanding change, demanding freedom. At that moment, I felt a spark of hope ignite within me, a belief that maybe, just maybe, the world I yearned for was within reach. We heard bullets firing into the crowd—one, then another—and the sweet scent of hope was soon overpowered by the smell of tear gas and the deaths of hundreds of students and protestors.

Sadly, the hope that once burned fiercely within me was squelched after the crackdown on the protesters in 2009. The government’s brutal suppression extinguished the flicker of optimism, leaving behind a lingering sense of hopelessness. But it was also in that protest, in front of Tehran University, that the seeds of rebellion were sown deep within me.

“Change Is Coming” by Leigh Brooklyn. Stencil vector art/digital illustration for street art, 2022.

“WOMAN, LIFE, FREEDOM” EXHIBIT / MOZAIK PHILANTHROPY

In 2022, after over a decade of stifled voices, the tragic killing of Jina Amini by the morality police for her “improper” hijab ignited a powerful uprising. Jina, a Kurdish girl, became a catalyst, inspiring the marginalized Kurdish community in Iran to spearhead a protest movement under the resounding slogan of “Woman, Life, Freedom.” They sparked a resistance that spread throughout the nation, drawing women, queers, and other marginalized groups from all corners of the country into the uprising.

The common thread that unites the rest of the women in Iran with the Kurds is their shared experience of being relegated to second-class citizenship. The struggle for equality and justice unites these groups as they advocate for their rights amidst the complexities of challenging, deeply entrenched patriarchal structures.

This uprising, rooted in Kurdistan and led by marginalized individuals, marks a distinct departure from previous movements in Iran. It bears the name “Zen Zian Azadi,” meaning “Woman, Life, Freedom,” drawing inspiration from both the feminist struggle and the Kurdish freedom movement. The powerful words of Öcalan resonate deeply: “A country can’t be free unless the women are free.”

“Hope” by Avin Abbasi. Photography, 2022. “Woman, Life, Freedom” exhibit / Mozaik Philanthropy

What captivates me the most is the embodiment of resistance, transforming the body into a battleground where norms are challenged. Dancing in the streets becomes a powerful act of defiance, a protest against a society that denies women their basic freedoms. Women cast aside their hijabs, symbolically liberating themselves from the chains imposed upon them. Some even go a step further, cutting their hair as a powerful act of protest against the regime’s policies.

In a society where dissent is silenced by state-controlled media, street art and social media emerged as beacons of resistance.

Before delving into the significance of art within this uprising, it is crucial to acknowledge two fundamental aspects that have shaped the nature and role of the art. First, the leadership in this movement is dispersed, not reliant on a single figure. It originates from the margins, where the oppressed gather strength and solidarity. Within the uprising, a remarkable form of leadership emerges—horizontal leadership—transcending conventional hierarchies and nurturing a collective spirit that empowers individuals to forge a path of change together. This inclusive approach fosters unity, collaboration, and a shared sense of responsibility, propelling the movement toward freedom and social transformation.

“Untitled” by Baset Mahmoodi. Photography, 2022. “Woman, Life, Freedom” exhibit / Mozaik Philanthropy

Second, a shift in the standard perspective on Iranian women is imperative. These women in the streets are not the oppressed figures often depicted by the world and media. It is crucial to see beyond the narrow lens through which they are often portrayed. They are not mere victims but fierce warriors, navigating a complex landscape with courage and resilience. The Western media and academia must recognize their strength and resist oversimplifying them based on the hijab, avoiding perpetuating stereotypes that limit their identities and overlook their complexity.

By acknowledging these factors, we lay the foundation for understanding the role and significance of art within this extraordinary, indigenous-led, feminist uprising. As I explore the role of repetition in the art of uprising and its connection to horizontal leadership, I will focus on two aspects that have deeply resonated with me: the body as the battleground and the horizontal web of art-making.

Body as a Battleground

In the face of bullets, arrests, and torture, the streets transformed into an alternative canvas for the message of the uprising. In a society suffocated by oppression, where archaic rules dictate every aspect of women’s bodies, dance emerged as a potent form of resistance.

It all began with a courageous girl, boldly moving and spinning with unwavering determination. As she danced, she symbolically set her hijab scarf on fire. Undoubtedly, many others had done the same, but it was the viral video of this girl’s act that became a catalyst. This powerful gesture ignited a revolutionary wave as people throughout the country joined in, dancing and following the score of liberation. Their bodies became the embodiment of resistance, every step in the dance a language of defiance. They shattered the stereotypes that portrayed them as passive and powerless, revealing the true strength that resided within them and their bodies.

Dancing and burning scarves in the fire became a symbolic act, repeated again and again, marking the end of oppression and igniting the flames of liberation. With each instance, the symbolism gained momentum and resonance. In the very streets where men enforced the wearing of scarves, the act of burning them served as a powerful reminder of their defiance.

“Baraye” by Shabnam Adiban. Digital art/animation still, 2022. “Woman, Life, Freedom” exhibit / Mozaik Philanthropy

Dance also possesses a contradictory nature within societal traditions. While Shia Islam has a strong tradition of mourning and sadness as a form of spiritual practice, the act of dance in this context stands in stark opposition. Dance becomes a symbol of joy, celebration, and resistance, challenging the narrative of sorrow and embracing the power of happiness.

Additionally, dance is a celebration of diversity. In a country where approximately 51 to 65 percent of the population are Fars, leaving almost half of the population marginalized, ethnic groups such as Kurds, Baloch, Gilaks, Turks, and Turkmen each bring their unique dances, representing their distinct identities and cultural heritage. Despite cultural assimilation and language restrictions, dance persists as a resilient expression of resistance and a celebration of diversity within Iranian society. “Baraye” (previous page), an animation by Shabnam Adiban, captures a poignant moment of Kurdish dance.

Horizontal Web of Art-making

During the Woman, Life, Freedom movement, I personally witnessed a remarkable shift in the art emerging from Iranian society within and outside of Iran, as non-academic and amateur artists’ works began to circulate widely on social media. It was a transformative moment that shattered the traditional hierarchy of art. It began with one person’s artistic response to a powerful photo on social media. Soon, others were compelled to join in, each adding their own unique twist and perspective to the evolving artistic expression, and all reacting to the same photo—the picture of a woman whose back was pock-marked with bullet holes.

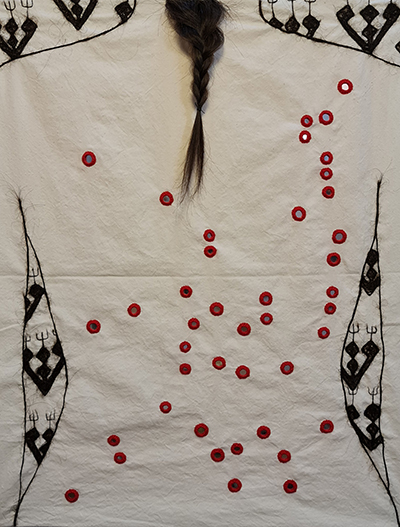

In “A Mirror in Front of You” by Mansooreh Baghgaraee (below) the artist ingeniously utilized embroidery, using the hair of protesters to form the shape of the girl’s body, while skillfully transforming the bullets into round Baloch-style mirror embroideries, creating a fusion of traditional feminine craftsmanship in service of resistance.

“A Mirror in Front of You” by Mansooreh Baghgaraee. Mirror embroidery and embroidery with natural hairs, 2023.

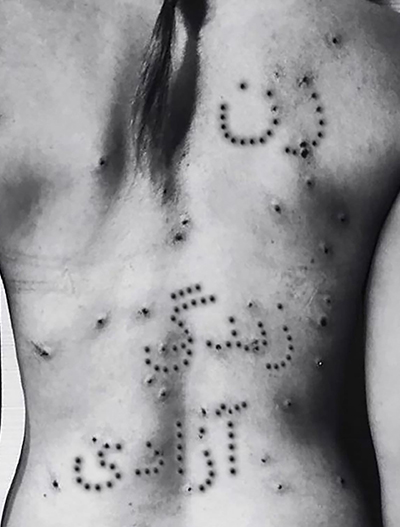

In “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” by Pedram Baldari (below), the artist followed a similar approach, integrating the original image while incorporating alphabetical representations of the bullets. Through skillful calligraphy, the bullets formed the slogan “Woman, Life, Freedom” in Kurdish. This choice of language added an additional layer of meaning and resonance to the artwork. The artwork’s powerful symbolism captivated viewers, evoking a profound sense of empowerment and resistance.

“Jin, Jiyan, Azadi” by Pedram Baldari. Digital art, 2022.

Each artist approached the creation of their artwork with a distinct choice of material, each intertwined with their unique history. In the first example, the female artist chose hair as her medium. By incorporating the hair of protesters, she not only added depth to the artwork, but it also carried profound symbolism about the ownership of the hair. Mansooreh Bagharaee captured the essence: “In my country, women’s hair carries tremendous political weight. Once severed and repurposed into wigs or brushes, it loses its inherent controversy. It seems that freedom is only granted in death, as the living are confined by societal constraints.”

In the second image, the Kurdish artist took a different approach, using the scars left by the bullet as the material for their artwork. This choice of material holds deep significance for the Kurdish people, as it reflects their enduring struggle and the wounds inflicted upon them throughout the history of the Kurdistan war in Iran. By incorporating these bullet scars, the artist not only visually represents their physical impact, but also symbolizes the resistance and resilience of the Kurdish people in the face of adversity. The artwork serves as a reminder of their ongoing fight for freedom and justice.

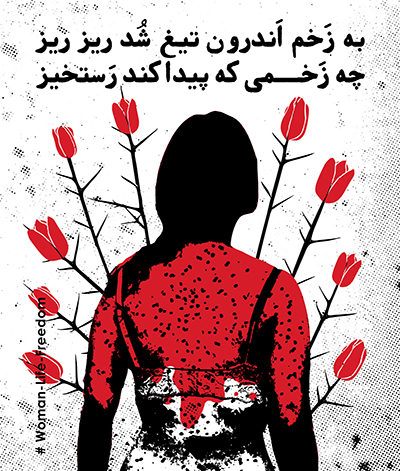

These two examples, among so many others, highlight the collaborative nature of the movement, as numerous anonymous protesters created variations of the same image, which artists eagerly embraced and interpreted in diverse ways. The images “The Shahnameh of the Iranian Revolution (Razor Growth From The Wound)” and “People” offer distinct artistic interpretations of the same type of photo, each adding significant meaning and depth to the visual narrative.

“The Shahnameh of the Iranian Revolution (Razor Growth from the Wound)” by Meysam Azarzad. Digital poster/graphic design, 2022. “Woman, Life, Freedom” exhibit / Mozaik Philanthropy

From “People” by Ghazale Bahiraie. Triptych Drawing/Ink on Board, 2022. “Woman, Life, Freedom” exhibit / Mozaik Philanthropy

This dispersed creative process fostered a sense of collaboration and challenged the art scene. Simultaneously, amidst the enthusiasm of the uprising, the crowd in Iran found a symbolic way to assert their ownership of the art of resistance. They took red paint, symbolizing blood and sacrifice, and marked the doors of prominent galleries that had opened their doors during the months of protest. This act was not necessarily an endorsement or disapproval of the galleries, but rather a powerful statement that separated the uprising’s art from institutional control and asserted the people’s claim over their own narrative. (It is important to note that my role is that of a witness, neither approving nor disapproving of these acts, but recognizing their significance in reshaping the art landscape).

Repetition in this horizontal web of art-making played a vital role in the uprising, reinforcing the significance of the image and its message. With each iteration, the impact grew stronger, reaching a wider audience and amplifying the voices of those fighting for change. This organic and collaborative process demonstrated the power of art to inspire and unite. As more individuals chimed in, the artwork multiplied and diversified, capturing the collective spirit of the movement.

Art and Hope

In the landscape of protest and art, a network of horizontal leadership emerged, interlacing voices and aspirations into a tapestry of collective action. And at its core, hope served as a guide. As Sahar Zand, the journalist and filmmaker expressed, “The authoritarian regime of Iran is clearly desperate to kill any and all hope. Because they know as long as we stay hopeless, we will resign to their oppression and injustice. But as history has shown over and over again, the light of hope emerges from the depth of the darkness.” May our streets bear new memories, as those on the margins tread a path to freedom by the light of hope.