“The very least you can do in your life is figure out what you hope for. And the most you can do is live inside that hope. Not admire it from a distance but live right in it, under its roof.” —Barbara Kingsolver, Animal Dreams

Until quite recently, discussions of hope in higher education have been scant. This is especially true outside faith-based institutions. In the wake of the global pandemic and related racial reckoning and financial crisis, conversations about hope are suddenly in vogue both in public and academic discourse. It seems hope talk is now everywhere.

For me, hope has been a recurrent subject of analytic curiosity and scholarly focus for almost 15 years. This fascination was sparked by reading Jonathan Lear’s 2006 Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation and shaped by Nancy Snow’s framing of hope as both an intellectual and a civic virtue. Hope is not a thing one had but something one did. It requires both courage and analytic rigor. It is both a way of seeing and a way of being. It is an epistemology.

In this edition of Virtues & Vocations, we share perspectives on how higher education ought to pursue human flourishing by grappling with the question of hope. In 12 essays written by scholars from around the country, an interview with philosopher Jonathan Lear, an art essay, and select poetry, hope is engaged as a virtue and as a vocation.

These often deeply personal and moving reflections provide both analytic insight and an invitation to a different way of being in the world that hope affords. But they each also make clear that hoping is hard and hope itself is often elusive. The different essays challenge us to understand how hope makes beauty, justice, grace, and compassion possible. They demonstrate how hope is integral to the good life. For Anika Prather, hope as a theological virtue is inextricable from faith and love. Reflecting on Thomas Aquinas and Iris Murdoch, Lydia Dugdale considers the way the virtue of hope is widely accessible. She writes, “People who seek to live and die well must become people of hope, moving toward the good and not withdrawing from it.” The essays also highlight how hope is enacted across professions such as business, education, engineering, law, and medicine. Of the care revolution in medicine, Victor Montori concludes: “In a bleak world riddled with invitations for indifference, hope emerges from the work of generous contrarians, who against all odds, reject the comforts of foolish optimism, and choose to care.”

In this way, several essays entreat a more profoundly hopeful world, a world reminiscent of Junot Diaz’s 2016 essay on radical hope: “This is the joyous destiny of our people to bury the arc of the moral universe so deep in justice that it will never be undone. Only radical hope could have imagined people like us into existence. And I believe that it will help us create a better, more loving future.” This kind of hope exercises both honesty and courage. As Rabbi Sacks reminds us in To Heal a Fractured World, this future world is one that requires more than simple optimism but the mettle and the shared struggle that hope demands.

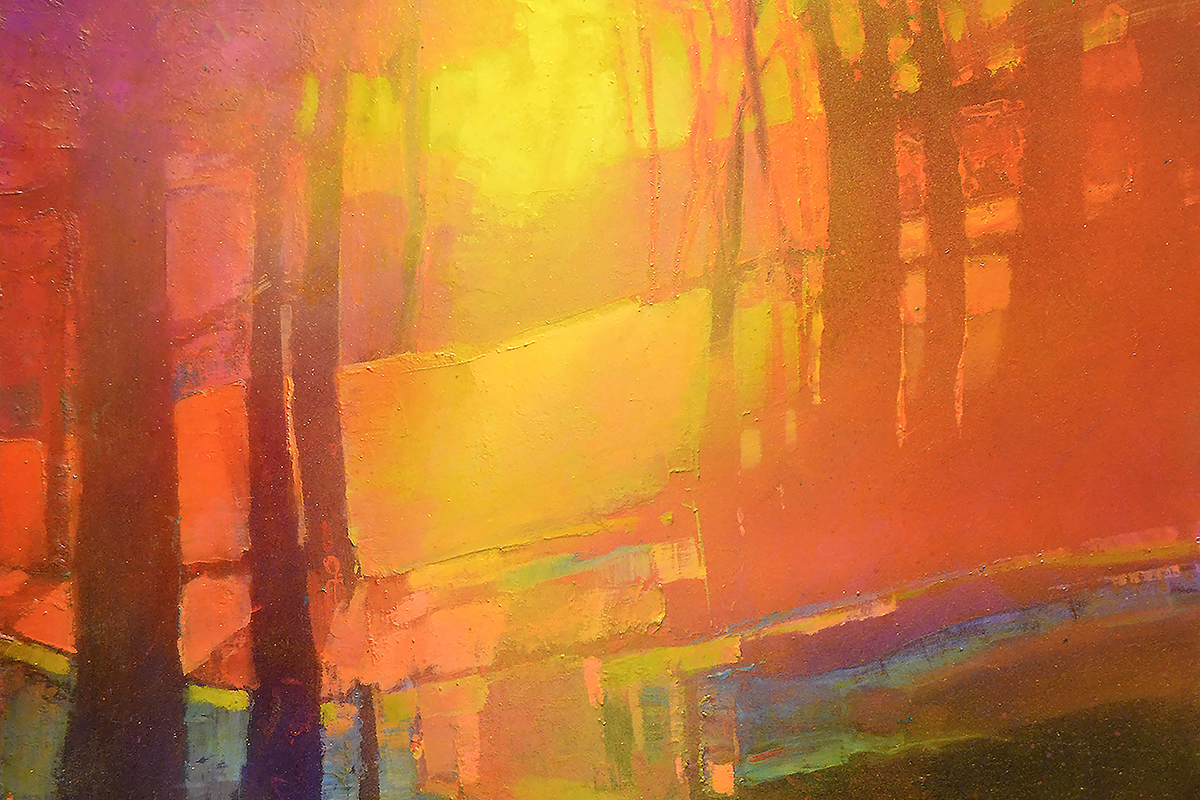

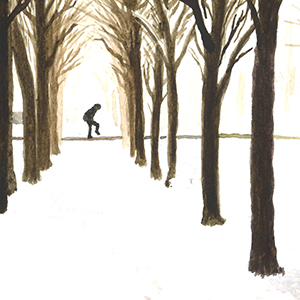

The art accompanying each essay plays with light in some way, framing hope as a way of seeing and understanding while exploring its complexity. Light, like hope, is intangible yet essential. It reveals what is true but can also bend and blind and redefine landscapes. Are the shapes and shadows an epiphany or distortion? Is the light producing illumination or imagination? As Michael Lamb reminds us, it is not just despair that opposes hope, but presumption. Norman Wirzba writes, “There is a fundamental blindness, even dishonesty, in the cheery optimist’s outlook because it does not properly name or adequately account for the injustices of the past or the present that are causing people to despair in the first place.”

Heeding this warning, this issue does not shy away from the existential issues confronting our students, our society, ourselves. Nooshin Javadi writes about the Woman, Life, Freedom movement in Iran and Margaret Hu outlines the existential threats posed by advances in Artificial Intelligence. We also feature a set of watercolors painted by inmates at the Westville Correctional Facility in Indiana, whose artistic practice illuminates the indomitability of human dignity.

In 2019, I designed a research study to understand how hope affected the subjective well-being of refugees from the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Burundi displaced in Rwanda. In some ways, these two groups have experienced the kind of dislocation and devastation that Lear details. I conceptualized hope as author and journalist Krista Tippet does, “Hope, like every virtue, is a choice that becomes a practice that becomes spiritual muscle memory. It’s a renewable resource for moving through life as it is, not as we wish it to be. . . . Hope is an orientation, an insistence on wresting wisdom and joy from the endlessly fickle fabric of space and time.” I asked how hope could both mitigate against despair and offer an understanding with which to move forward in the face of profound displacement. This study was only one of many efforts derailed by the COVID-19 pandemic, left aside for another time. But understanding the role of hope in everyday life is a question that continues to animate my own scholarship, teaching, and being, thus making this edition of Virtues & Vocations particularly instructive and inspiring. We hope it provides readers a similar opportunity for reflection.

–Suzanne Shanahan