About a decade ago, a group of us imagined a healthcare system focused on care. This system would allow clinicians and patients to co-create, within relationships of trust and unhurried conversations, evidence-based treatment plans that could improve each patient’s situation. What was unusual for those involved in that moment was our decision to not just imagine that future, but to begin the long and arduous process of making that future a reality. What this group harnessed when we chose to go after this utopia, that is hope.

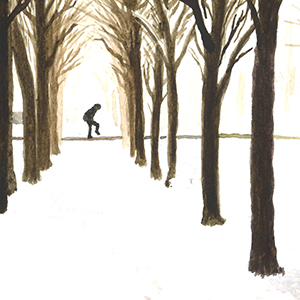

At a workshop, a student asked the filmmaker Fernando Birri what utopias were for. Utopias, he replied, are in the horizon. If I take 10 steps toward the horizon, the horizon will take 10 steps back. If I take 20 steps forward, the utopia will be 20 steps further away. I know very well that I will never ever reach her, he continued. So, what are utopias for, you ask? Well, for that. Utopias are for walking.1

Hope is born with the purposeful choice of taking the first step toward the horizon. Hope grows as feet stride. Hope matures in the face of the horizon’s retreat. Hope is wishful walking.

Hope that things will be better in the future rests on actions taken today. To care for the seedlings, the gardener must hope for a lovely flower or a juicy fruit; her care of the seedlings, in turn, will sustain that hope. The seeds, the dirt, the light, the water, and all that care still offer no guarantee of success. And yet, hope springs from the time, energy, and attention invested in tending to those seeds, from the ongoing care to optimize the conditions for their growth.

Hope and care are inextricably connected. A member of the Iroquois nation could leave their home and travel far away, knowing that, upon encountering a group from another nation, they would be welcomed as visitors and receive food and shelter. That expectation of care mitigated the traveler’s risk and fueled hope in completing the journey.

When people facing disease and disappointment approach healthcare, they expect care. The patients I am privileged to meet often have diabetes and other ongoing conditions. They have no foreseeable path to a cure; they will instead live with their conditions and their complications. Tending to these conditions is a continuous and never-ending slog for them and their families. To access healthcare, patients and caregivers must navigate systems with features that bely the designer’s indifference to their needs, or their incompetence in meeting those needs, or their inability to overcome the competing financial goals and objectives of the system. Expert advice, medications, and technologies may improve the patient’s situation, but the work to access and use this care often exceeds the capacity patients and caregivers can mobilize for this purpose. Were they to receive care, it will not just be burdensome but also generic—not for you, but merely for people like you.

This will be worse for those living in conditions of socioeconomic deprivation. These patients will accumulate more chronic conditions starting at an earlier age and at a faster rate than their wealthier peers. They will have fewer resources to mobilize for self-care and to access healthcare; their efforts consumed instead in the hard work of surviving. The healthcare they receive is often scarce, unaffordable, and substandard. In many cases, they are greeted with the cold blade of cruel indifference where the wounded traveler would have expected the warm embrace of the brother and sister from a caring nation. Sick, exhausted, uncared for, their feet drag as their own horizon runs away from them. Despair.

Thus, like fortune and opportunity, hope is also unequally distributed. This results in pessimism for most — there is nothing you can do about your situation is the message that many receive. The social media doom-scroll reinforces this anxious sense that the world is in a bad way and can only worsen. Why not consume instead the always-on-sale wares of opportunistic politicians and corporations: the optimism of their brands, products, and promises? Optimism is opium for the people. Optimism invites people to work hard and consume harder while things get better on their own. It convinces people to wait in their stuporous, obesogenic, lonely, and networked state for the arch of justice to bend in their direction. By normalizing inaction, optimism prevents people from mustering the motivation to walk, robs them of hope. Sedated by pessimistic anxiety or reality-free optimism, many stop walking, dying deaths of despair.

A healthcare that cannot cultivate care, that is cruel and overwhelms clinicians and patients, is in desperate need of fundamental reform. The possibility of a better healthcare system in the future emerges from people noticing this desperate situation and responding to it by choosing to work to change it. The possibility of better emerges from the action of people who choose to care. Because we live in complex and interconnected worlds, these change makers cannot predict the full extent and effect of their actions. Perhaps it is naïve to expect a better tomorrow, but today’s efforts may just create the possibility of one. Care engenders hope.

About 10 years ago, a group of us imagined a healthcare system capable of cultivating care. We imagined that utopia and chose to walk towards it. We announced that healthcare had become industrialized, carelessly processing people. That it had corrupted its mission, that it had stopped caring. That we had to work to turn away from industrial healthcare and toward our utopia—careful and kind care for all. As the industry celebrated its technological prowess and millions were invested in the sector, no effort, at scale, was in place to overcome its corruption, to turn away from industrialized healthcare. We decided to revolt.2

This decision catalyzed the formation of an organization comprised of patients and healthcare professionals from around the world, committed to action, to walking.3 These care activists recognized that a clinician cannot care for a patient that is only viewed as a diagnosis, a test result, or a medical history. Care has its own rhythm, a helpful dance that, when accelerated, becomes useless convulsion. These pathologies of care, fueled by efficiency and expediency, needed to be called out for what they were for the revolution to follow. And so, in our own small ways, we started to do just that, naming and transforming the toxic elements of healthcare that ultimately got in the way of caring for patients.

Wherever they take place, these mini revolts seek to implement the proposals of our movement for care. There, care activists notice the problematic situation and choose to invent a response to it, one that promotes careful and kind care for all.

In inner city London, a small, disused, urban courtyard in the premises of a clinic was transformed into the “Listening Space,” a lush garden in which a community of people could gather, share their stories over a meal, and care for and about each other. Clinicians often walked through it with patients facing a difficult situation, having unhurried conversations about how to best move forward.

Online, a global community has gathered to have a monthly “Conversation for Kindness,” discovering and sharing ways to find and introduce kindness—starting, for example, with “what matters to you” rather than “what is the matter with you”—into health care.

Academics have written papers describing what healthcare leaders can do to bring about organizations and clinics able to foster careful and kind care. An international collaboration published the “Making Care Fit Manifesto,” calling for patients and clinicians to work together to form individualized plans of care that minimally disrupt the lives of patients and their loved ones.

The work of care activists has started to influence policies for care across the world, including the Realistic Medicine program of patient-centered care in Scotland. Schools are beginning to teach the lessons we have learned to ensure that upcoming generations of healthcare professionals know that a healthcare capable of care is possible, feasible, and desirable. These mini revolts are hopeful steps toward a utopia of care.

As they gather on the road, care activists give each other courage, knowing full well that what they may see yonder may be a mirage, that failure remains the most likely outcome. And yet, that they must keep walking.

Hope is wishful caring. Caring, choosing to respond to suffering and despair, creates hope for relief and healing.

In a bleak world riddled with invitations for indifference, hope emerges from the work of generous contrarians, who against all odds, reject the comforts of foolish optimism, and choose to care.

Care to hope.

Notes

- As told by the Uruguayan writer, Eduardo Galeno.

- My motivations for this revolution can be found in, Why We Revolt: a patient revolution for careful and kind care. 2nd edition, 2020. Mayo Clinic Press.

- The Patient Revolution, patientrevolution.org.