As a medical doctor who cares for older and ailing patients, I have long struggled with how to inspire hope when the medical facts paint an otherwise grim picture. In the face of imminent death from cancer, a fatal drug overdose, or a devastating injury—what can a doctor say about hope in such cases that is not mere platitude?

When I was a young physician, I secretly rolled my eyes at doctors who encouraged their patients with terminal diagnoses to tackle bucket lists, as if seeing the Grand Canyon or tasting chocolate ice cream one last time were sufficient salves for mortal wounds. We doctors decry the suggestion of giving patients false hope, but then we offer patently sugarcoated alternatives. Surely, we can level with our patients, my younger self would think. Surely, the sick and dying deserve a robust hope.

To be fair, there’s nothing wrong with setting more modest goals for oneself as the trajectory of life changes. I’ve cared for many adult patients with disabilities, for example, whose family members have had dramatically to re-imagine their lives in order to care for children-turned-adults with special needs. Although such changes of plan often endure for decades, they can be no less drastic in the face of a terminal diagnosis or sudden death. Shocking events demand a reckoning by all affected. So, bucket lists and chocolate ice cream are fine, but they are not enough. Health care professionals can do better at instilling hope in the face of sickness and death.

That doesn’t mean there’s a clear path forward. In our pluralistic world, hope and meaning can be dialed up or down depending on culture, ethnicity, community, or other sources of identity and belonging. Some individuals no longer rely on social groups to help them make sense of life’s deepest existential questions. Instead, widespread assent to radical self-determination and “you do you” rhetoric, combined with a pluripotent social media, mean that people can believe everything or nothing on a whim and without substantive accountability.

In my book The Lost Art of Dying: Reviving Forgotten Wisdom,1 I describe a genre of literature called the ars moriendi, or art of dying, that was first popularized in the late Middle Ages and circulated for about 500 years. The ars moriendi were handbooks on the preparation for death. Earliest iterations generally taught that the dying faced five primary temptations or vices—doubt, despair, greed, pride, and impatience. To die a doubting, despairing, greedy, prideful, or impatient person was to die poorly. And the best way to counter these vices, the handbooks taught, was to cultivate their reciprocal consolations or virtues—faith, hope, generosity, humility, and patience. Becoming generous or patient wasn’t work to save up for the end of life, however. Rather, to die well, one had to live well. And living well meant practicing the virtues over the course of one’s life in the context of community. After all, the good life (and a good death) could only be understood communally.

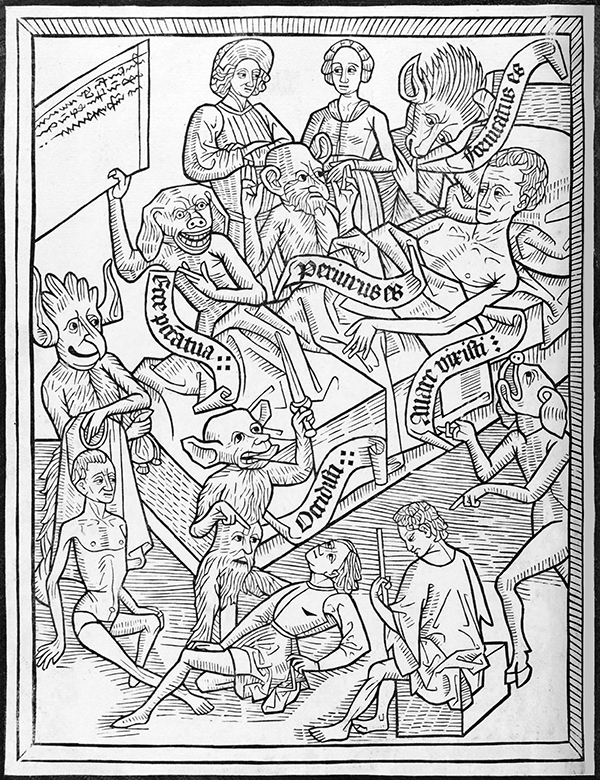

Figure 1. “Temptation to Despair,” Ars moriendi, Germany 1466. Library of Congress

Most Western Europeans of the late Middle Ages, however, could not read. The faithful thus learned their theology not from text but through participation in services and liturgical practices, as well as through art, icons, altarpieces, and other religious visual imagery. Accordingly, there began circulating by 1450 an illustrated version of the ars moriendi containing 11 images that paired the 5 temptations to dying poorly with their respective virtues. Throughout the first 10 images, it is clear from representations of angels and demons that a battle wages for the dying man’s soul. The eleventh image illustrates the dying man’s moment of death, victorious over the forces of evil. For our purposes, consider the images of despair and hope.

Figure 1 depicts the temptation to despair. The dying man lies in bed, surrounded not by loved ones but by reminders of past indiscretions. What is more liable to drive a person to deep hopelessness than a room full of beings reminding him of the myriad ways he’s hurt others? He’s an adulterer! Or so says the figure in the image at 11 o’clock, accusing the dying man of adultery and bringing a woman as proof. The accompanying scroll, in Latin, says it all: Fornicatus es.2 What’s more, he’s greedy! The demon at 3 o’clock suggests as much and points out a poor, dejected man on a box, presumably in need because of the avarice (Avare vixisti) of the dying man. In the lower left corner, there also sits a man thought to be naked because of poverty. The demon attending him clutches a bag of money, again reinforcing the greed of the dying man. Other demons indicate other failures: Murder (Occidisti)! Perjury (Perjurus es)! And if that’s not enough, there’s a host of other sins (Ecce peccata tua) scribbled on a board. Such damning taunts are enough for the dying man to despair of his hopeless condition.

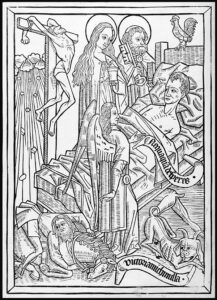

But it is the aim of the ars moriendi genre not to leave the viewer in a state of despair. To die despairingly is to die poorly. Instead, the dying man must cultivate hope, and those attending him must also cultivate hope while they are living and well. In Figure 2, Comfort Through Hope, an angel encourages him not to despair. “Hope is possible, after all,” writes the theologian Allen Verhey. He continues:

And the evidence surrounds the bedside. There they are, sinners all, brought through the judgment by the grace of God. Is the accusation fornication? But there is Mary Magdalene, with her reputation as a sinner. . . . Is the accusation avarice? But there is the thief on the cross. Is the accusation murder? But there is Paul . . . struck down from his horse on the way to Damascus to persecute and kill. And is the accusation perjury? But there is Peter, holding the keys of the kingdom. . . . And there in the background are the heavens opening, with a path for sinners.

Here is proof that no matter what he’s done, hope is possible. And the defeated demons go slinking off.

Figure 2. “Comfort through Hope,” Ars moriendi, Germany 1466. Library of Congress

In The Lost Art of Dying, I posit that we moderns would die better were we to revive the wisdom of the ars moriendi. If that’s true, and if it makes sense for doctors to encourage their sick and dying patients and their communities to practice hope, this prompts another question. What do we mean by hope?

Hope has been defined in myriad ways, but if we’re going to draw from the ars moriendi as a medieval commendation to practice hope over a lifetime, and even in the face of death, it makes sense then to consider an account of hope from that era. Perhaps best known among thinkers of the Middle Ages is the philosopher and theologian Thomas Aquinas, whose work on hope draws broadly from thinkers, both his predecessors and contemporaries.

The virtue of hope, for Aquinas, is a theological virtue, meaning that it is given by God. Hope is the second of the theological virtues—nestled, as we find it, between faith and love.3 According to Aquinas, hope leans on God’s help to obtain the difficult to achieve but possible future good of eternal happiness with God in Heaven.4 Since God’s very essence is goodness, ultimate happiness comes from union with such an infinite good.5 By contrast, desperatio (despair or desperation) derives its name from being contrary to spes (hope).6 Aquinas says that despair is not only the opposite of hope, but also the withdrawing from hope.

As is the case today, not everyone believed in God in the late Middle Ages. Does Aquinas then have an account of hope for the non-believer? In fact, he does. His non-theological ordinary hope is not a God-given virtue, however, but a passion or emotion natural to human beings. By passion, Aquinas suggests a certain passivity—passions happen to a person. Just as a hankering for a hamburger happens to a person, so too does hope—an appetite for the good.7 Hope regards a future good that takes some work but is possible to obtain.8 It is not for things we already have or for bad things or for things that are trivial or impossible to attain; hope is the expectation for a future arduous good that is within the realm of possibility. It is a familiar, natural hope that belongs to earthly life now.

But here we face a dilemma. Although the ars moriendi texts taught that both the living and dying could cultivate hope to mitigate the possibility of a life and death of despair, the earliest versions assumed a theological virtue of hope—hope for the happiness of Heaven—not an ordinary natural passion or emotion of hope. But just as all versions of the ars moriendi did not remain under the banner of Christendom, neither did all its practitioners. And as the ars moriendi secularized, there arose a need for an account of hope as a virtue that did not necessarily culminate in union with God, along with a way of thinking about hope as a virtue that one could nurture and not just passively experience.

Scholars after Aquinas debated among themselves whether hope is in fact a virtue and whether it can be cultivated independently of divine assistance. If hope has no ultimate fulfillment (such as union with God), does it lose its relevance? Or can human beings rationalize their way to hope? And so forth. But these were questions for the learned elite and not for the average inhabitant of Western Europe during the late Renaissance.

Commoners on the whole had more pragmatic considerations: “If we don’t want to die as greedy despairing fools, how then do we exercise generosity and hope throughout our lives?” Answering questions such as this didn’t necessarily require the divine; it required good habits. But habituating to virtue takes work. As the sixteenth-century philosopher and theologian Erasmus puts it, “This preparation for death must be practiced through our whole life. . . . [A]n action continually repeated will become a habit, the habit will become a state, and the state become a part of your nature.”9 His contemporary Robert Bellarmine sums it up simply, “He who lives well will die well.”10 If you want to be a person of hope, you have to practice it. It is not enough to wait passively for the appetite of hope to come upon you. If you want hope in the face of death, you have to repeat it continually until it becomes a part of your nature. But what does practicing hope look like for the person who rejects the idea that hope’s fulfillment is eternal happiness with God in heaven?

I want to suggest two answers. First, the nonbeliever may depend on others to exercise hope. Although Aquinas acknowledges God as both the ultimate hope and divine assistance as what he calls “the first cause” leading to happiness, he is clear that one can place one’s hope in a person or a creature as what he calls the secondary or instrumental agent through whom one is helped to obtain the good.11 That’s why, he says, we ask others for help; our hope is that they will help us reach a place of flourishing. So, nonbelievers can practice the theological virtue of hope by proxy, through community. And we see this in the hospital where the dying may ask their loved ones or the family priest to hope and pray on their behalf, when they themselves cannot hope.

Second, it is possible—although perhaps not acceptable to orthodox Christians—to decouple the notion of the Christian God from the idea of the infinite good. As we have said, Aquinas’ virtue of hope leans on God’s help to obtain the future good of eternal happiness with God in Heaven, and since God’s very essence is goodness, final happiness comes from union with this infinite good.12 If we break this down into its components, Aquinas’ virtue of hope could be said to require:

- God’s help, or divine grace

- An infinite good as its object

- Future fulfillment

The question then becomes whether we can find a satisfactory non-religious accounting of grace, the infinite good, and future fulfillment that can do the work of the (theological) virtue of hope.

The philosopher Iris Murdoch was interested in the possibility of an infinite good separate from religious notions of God. Let’s now consider how Murdoch might explain each of these three components of the virtue of hope using her non-religious concept of the sovereignty of the good.

First, in Christian parlance, ‘grace’ is often defined as unmerited favor, good will, or blessing. It is a form of gift that one receives; or, as Aquinas puts it, grace signifies something bestowed on a person by God.13 Murdoch says that the “concept of grace can be readily secularized,” by which she means that we can expect to “receive a return when good is sincerely desired” that does not come from the divine.14 She also describes grace as “an unforeseen reward for a fumbling half-hearted act.”15 In contrast to Aquinas, who suggests that divine grace precedes human ability to hope for the good, Murdoch seems to suggest that the orientation of human hearts toward the good results in grace as a sort of return on our investment in the good. Although this grace is post hoc, I here suggest that there’s no reason to assume that the recipient of such post hoc grace can’t “pay it forward”, thereby facilitating the hope of another. For example, if a child witnesses the grace in her mother’s life as a result of her mother’s hope for the good, that child can build from that foundation of grace in her own hope for the infinite good. Murdoch’s notion of post hoc grace can thus become the grace that precedes another’s habit of hope.

Second, the virtue of hope requires the infinite good as its object. And on this point, Murdoch’s work shines brightest. She says, “Good is the focus of attention when an intent to be virtuous coexists (as perhaps it almost always does) with some unclarity of vision.”16 Although she does not here speak specifically of the virtue of hope, she is discussing the virtuous life more broadly—that is, the life oriented toward human happiness—and she ties it to an ill-defined future good, the same object for Aquinas’ ordinary (non-virtue) of hope. She anticipates that some might say,

>It makes sense to speak of loving God, a person, but very little sense to speak of loving Good, a concept. ‘Good’ even as a fiction is not likely to inspire, or even be comprehensible to, more than a small number of mystically minded people who, being reluctant to surrender ‘God’, fake up ‘Good’ in his image, so as to preserve some kind of hope.17

Murdoch says that she herself is half inclined to think in such terms. Yet, she continues to believe that “there is more than this,” that some “very tiny spark of insight” is real.18 Although she says she refuses to believe that the Idea of the Good exists “as people used to think that God existed,” she nevertheless insists that “[t]he image of the Good as a transcendent magnetic centre seems … the least corruptible and most realistic picture for us to use in our reflections upon the moral life.”19 Murdoch’s infinite Good is not God, but it can indeed be the object of human longing and attention, and it can, she suggests, provide moral clarity.

Third, the virtue of hope—as with its ordinary or natural counterpart—requires future fulfillment. Since futurity is neither theological nor secular, we need not flesh it out further. However, a metaphor from Murdoch helps to pull together the whole account of a secular virtue of hope.

Recall again the idea of habituating to hope for a future good that is arduous but possible to attain. This future good is infinite, poorly defined, but draws us toward it. Hope, then, can be understood as the habit of orienting time and time again toward that supreme good, recognizing that some sort of good grace will return to us even as we practice leaning in toward the good. Murdoch says this is very much the action of the artist, who “is obedient to a conception of perfection to which his work is constantly related and re-related in what seems an external manner.”20 The artist works toward the ill-defined good that “lies always beyond, and it is from this beyond that it exercises its authority.” It would here be foolish to suggest that the artist is exercising the passion or emotion of hope as he applies stroke after stroke to his canvas in pursuit of the good. Rather, the artist has cultivated the virtue of hope that holds out for a future good that is elusive yet possible to attain.

Murdoch, born into a family of Presbyterian and Church of Ireland extraction, is never very convincing in her rejection of the possibility of God. Although her account of the Good as replacement for the idea of God can helpfully cast the theological virtue of hope into quasi-secular terms, the student of Murdoch is left wondering whether she is on to something when she says, “there is more than this.”

The theologian Andrew Pinsent raises the same question in different terms. He notes that the language of hope is everywhere in secular spaces, not least the supermarket and retail shops. He writes:

I have found many goods that offer, for example, “snacking nirvana,” or “bliss,” or “paradise,” or “heaven,” or products, such as from a famous coffee company, that promised to warm my soul, not just my stomach. The prevalence of this soft-focus religious language, to sell everything from holidays to oatmeal, witnesses to a confidence that human beings have at least an inchoate desire for the happiness of heaven regardless of their personal religious commitment.21

Although Pinsent suggests that such consumerist references to hope belong to the passion of hope rather than the theological virtue, one might argue that other expressions—such as the Good sought by Murdoch’s artist—suggest a virtue of hope that can be practiced time and again as the artist approximates to the Good.

Murdoch’s Good—in contrast to Aquinas’ God—is not knowable. It’s very clearly not a god who invites his creatures into a relationship of eternal happiness. Still, Murdoch maintains that “there is a place both inside and outside religion for a sort of contemplation of the Good.”22 Hope for the Good is not mere platitude—that is, it’s not chocolate ice cream or the Grand Canyon. Rather, Murdoch says, it’s hope for “a distant transcendent perfection, a source of uncontaminated energy, a source of new and quite undreamt-of virtue.”23

Religious or not, people who suffer—which at some point includes all of us—need to be able to practice the virtue of hope, to move toward the good, even if it takes hard work and even if it is difficult to attain. Anything less is to leave people to despair, which serves no one. The appeal of the genre of literature is that it offered guidance to communities in the form of an art of dying that was best understood as an art of living. People who seek to live and die well must become people of hope, moving toward the good and not withdrawing from it. Whether the infinite good is ultimately unknowable remains to be determined by each of us in our communities. But one thing is nearly certain. If we don’t make a habit of moving toward the good, we may never discover whether the good is, in fact, God.

The author wishes to thank John Hare, Ashley Moyse, and Benjamin Parviz for advice on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Notes

- L.S. Dugdale, The Lost Art of Dying: Reviving Forgotten Wisdom (NY: HarperOne, 2020).

- I’m grateful to Allen Verhey, The Christian Art of Dying: Learning From Jesus (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2011) for his clear explanation of these images.

- Thomas Aquinas, ST II–II, q. 17, art. 5.

- ST II–II, q. 17, art. 2-3.

- ST II–II, q.17, art. 2.

- ST I–II, q. 40, a. 4.

- ST I–II, q. 22, art. 2.

- ST I–II, q. 40.

- Erasmus, “Preparing for Death” (1553), in Collected Works of Erasmus: Spiritualia and Pastoralia, ed. John W. O’Malley (Toronto: Univ of Toronto Press, 1998): 392–450, 398, and 421. As quoted in Allen Verhey, The Christian Art of Dying: Learning From Jesus (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2011): 255.

- St. Robert Bellarmine, The Art of Dying Well (or, How to Be a Saint, Now and Forever) (Manchester: Sophia Institute Press, 2005), 3.

- ST II–II, q. 17, a. 4.

- ST II–II, q. 17, art. 2-3.

- ST I–II, q. 110, art. 1.

- Iris Murdoch, Sovereignty of the Good (London: Routledge Classics, 2001): 62.

- Murdoch, 42.

- Murdoch, 68.

- Murdoch, 70.

- Murdoch, 71.

- Murdoch, 73.

- Murdoch, 61.

- Andrew Pinsent, “Hope as a Virtue in the Middle Ages” in S. C. van den Heuvel (ed.), Historical and Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Hope, doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-46489-9_3.

- Murdoch, 99.

- Murdoch, 99.