Inclusivity, change, and hope

By: Mary Ellen Woods ’80

May 16, 2024

“It’s hard to imagine that’s how the school (ND) was in the past, so it’s interesting to think about how much more it will change over time.”

Samuel De La Paz ’22

Notre Dame in the mid-1980s was a different place. New to coeducation, women comprised less than 30 percent of the student body. And racial diversity, save for a few exceptions and the presence of student-athletes, was not a primary focus. Numbers are only one and generally an inadequate measure of change or the degree to which an organization embraces those who are new or without precedence. By contrast, and from its very founding, the Institute for Social Concerns was a place where all were welcome, and minority groups often gathered. In more recent years, the University has taken active and welcome steps to center all students in Our Lady’s embrace. We are seeing increasing racial and economic diversity among the entering first-year classes.

The process of writing center alumni stories has led me to an observation that the center has long been a more inclusive space than the broader Notre Dame community. Since its founding in the early ’80s, it has welcomed a wider range of students who differ in race and life and college experience from their fellow students. They are motivated to learn and serve those who may even be different from themselves. To explore my notion and to learn more, I engaged in a virtual conversation among center alumni of different eras, experiences, and perspectives. Our conversations led me to a richer and more promising understanding.

My sense is that the center — grounded as it is in the tenets of Catholic social teaching — is participative, shows solidarity, and is welcoming to all, both current ND students and those with whom they would study and work in the classroom and the field.

The alumni

Micah Burbanks-Ivey came to ND from San Jacinto, a small town in southern California. He majored in political science and economics and graduated in 2015. He became involved in the center freshman year, after attending an event at the center discussing social activism. The diversity in the room as compared to the wider campus was palpable for Micah, who is African American and not Catholic. The center was his first introduction to Catholic social teaching. “A doctrine of activism with the life and dignity of a person, regardless of their socioeconomic status, and faith as a focal point was not something I could forget. It motivated me to want to do more,” he said. “I think the Institute for Social Concerns is more inclusive because it centers on justice, inclusiveness, equity.” Micah went on to Harvard Law School and continues to advocate for others.

Erica Browne comes from a family of Liberian immigrants. She was born and raised in Oklahoma City. She graduated in ’22 and plans to attend medical school to pursue a career in psychiatry. She felt a need to feed her soul and to lean into passions beyond neuroscience which led her to apply to a seminar course entitled “Organizing, Power and Hope.” In Erica’s words, “Applying to participate in that seminar was the best thing I could’ve done for myself. I learned so much and it led me to do some really amazing things.” She participated in additional Institute for Social Concerns seminars and summer programs, and was an Andrews Scholar. Erica highlights an important point about the center. To her, it was no more diverse than ND as a whole. She found both to be extremely white spaces. The center, however, was a safer space for racial and ethnic minorities on campus and the courses created an environment for white students that were more comfortable with diversity. She noted, “The faculty at the Institute for Social Concerns all were amazing examples of people that live their lives in service to community.” Erica has made it her mission to strive to do the same.

Rocio Aguinaga ’10 first came to the center during his first year. The center’s space housed the Chicano Student Movement of Aztlán (MECHA) meetings he joined. “Sophomore year I finally decided I needed to do something with my break and felt the Institute for Social Concerns was an economical way to travel and learn. I had no funds to do anything else.” Rocio ultimately traveled to Appalachia during fall break of his sophomore year. In the summer, the Latino Leadership Internship Program (LLIP) allowed him to work with a nonprofit in the suburbs of Chicago where he helped people pass their citizenship exam, a milestone he helped his parents reach years earlier. Another reason the LLIP was a formative experience is that it enabled Rocio to meet the center’s founder, Fr. Don McNeill, C.S.C., and establish a relationship with him. Rocio also participated in the “Migrant Experiences” course junior year. When I asked Rocio if the center is more inclusive than ND at large, he said: “Yes and no.” It helps bridge the gap of helping students get out of their own heads and experience. It also helps break barriers and bond the students outside of the classroom. “I think that the CSC is a critical part of making ND what it is.” Rocio majored in finance with a supplementary major in Latino studies and a certificate in international business.

A 1985 American studies grad, Marybeth Christie Redmond noted: “The Institute for Social Concerns was one of the more diverse spaces on campus, attracting students from varied cultural backgrounds.” Redmond was one of the earliest center participants. Initially she participated in an Urban Plunge in the South Bronx, NY. She describes the South Bronx as a very poor, war-zone-like place back then. Economic inequalities have always resonated at the center, where students are exposed to poverty through their service and studies in the classroom. Marybeth echoed a familiar refrain in describing her interactions with Mary Ann Roemer, who seems to have frequently guided students to service or scholarship, and Fr. Don McNeill, C.S.C., a founder of the Institute for Social Concerns and a friend to all who knew him.

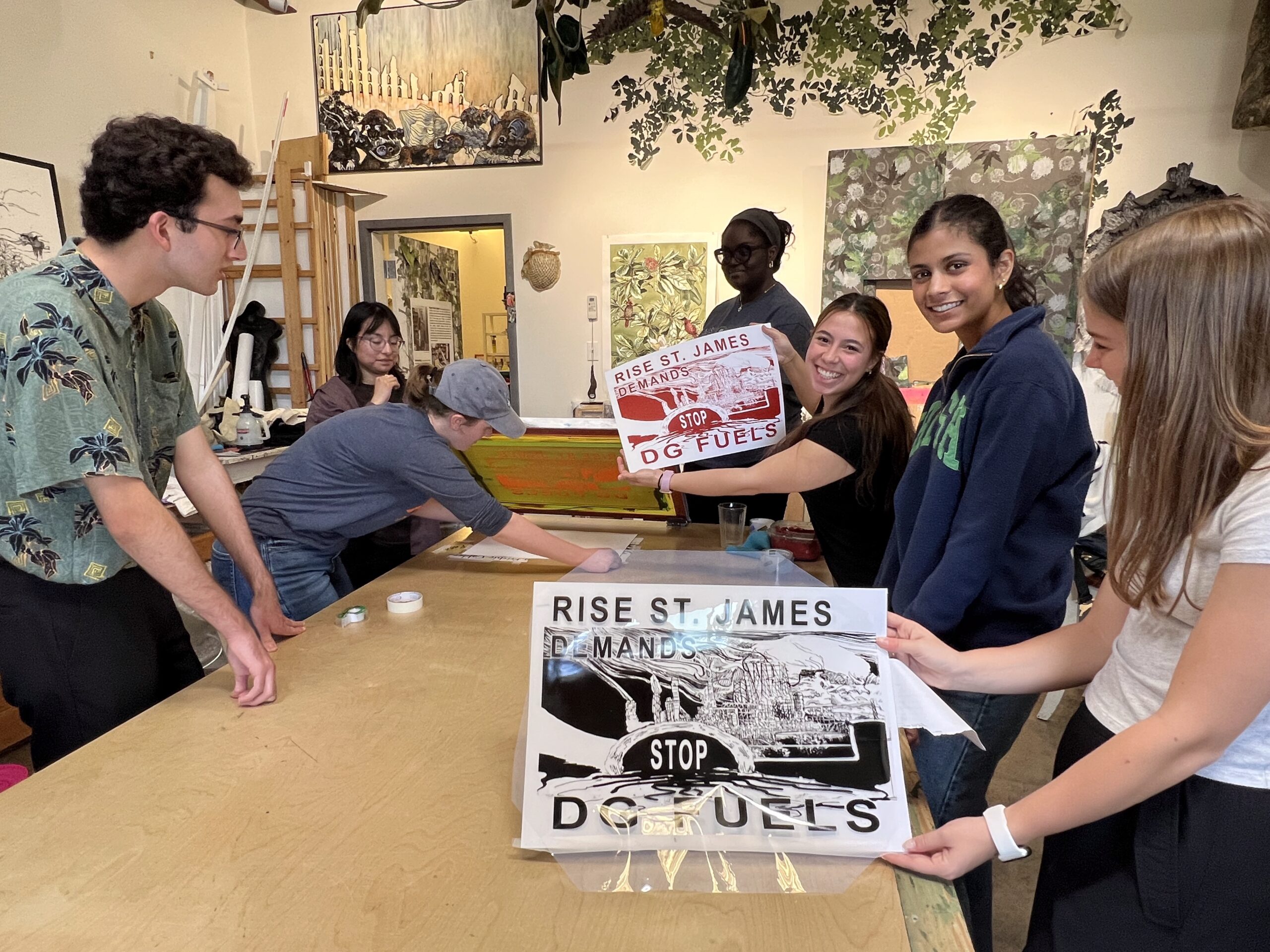

Samuel De La Paz, from the class of 2022, offered the quotation I cite above. I was explaining to him that I was in the very early days of coeducation. His insights demonstrate the wisdom of a Institute for Social Concerns experience and offer hope for our beloved University and the world beyond. Samuel studied mechanical engineering, traveled to Appalachia for the fall break seminar course, and was a participant in the McNeill Fellows program. He reflects both the inclusive nature of the center and the progress ND has made over time. His is not a wistful hope for the future, rather he speaks in the present of the “center drawing a diverse crowd that brought many perspectives to conversations around justice, and created a safe place for people to have hard conversations about racism, inequality, privilege, and other politically tense topics.”

My learnings

The alumni with whom I talked had experiences and insights as varied as their ND educations and lives before and after college. For some, the center was a respite from the whiteness of the ND population and perspective. Others were attuned to economic inequalities manifest among the poor. What I was especially struck by was the common experience most shared in the classroom: That the center shaped what and how they studied about race and inequality. Seminar courses offered students opportunities to explore theory and how they applied it in the field. The most compelling learning, and one that resonated with everyone I talked with — both for this piece and the others before it — has been the lasting and formative affect the center has had on all who participated. The range of students who engage is wide, their experiences varied, and yet, it is inextricably shaped by time spent around the center.

Through the experiences and reflections of these alums, I learned that the center drew students to it, often in their early days at ND. Sometimes it housed a specific program or destination. Other times, the students realized that they were either missing something in their college studies or specifically wanted to broaden their experience. The center offered both academic and experiential opportunities that exposed students to wider realities and the place to study and discuss them. I was also struck by how “sticky” the center seems to be. Students who sought it out, or gravitated to it early in their college experience stayed. And the center stayed with them. Each alum with whom I talked could easily describe how the center still resonated in their lives, be they recent grads or alums hailing from the ’80s. I suspect that I knew this, but it is heartening and probably informative to contemplate the many reasons students’ relationships with the center are so lasting.

If I could, I would include insights from each of the alums I’ve talked with in this pursuit. Each spoke eloquently of her or his experience. Narrowing my selection as I must, I’ll share Micah Burbanks-Ivey’s: “I went to Notre Dame to expand my horizons as it relates to culture and religion. While I reached that goal, often as a minority student from a low-income background, it was easy to feel isolated. The diversity of the center, the passion of its students and faculty, and its focus on advocacy on the types of low-income community I come from, reminded me of home.”

In this case, we have met a finance major, a journalist, a lawyer, and an aspiring doctor. They hail from the ’80s through the most recent of grads. Race and gender are well represented (though women do seem to be drawn in large numbers to the center). Each has had a learning experience that has helped form them both during their time as students and on campus. Their center experiences are both profound and durable.

Related Stories

-

Toward a culture of encounter—Lecture series engages Pope Francis, Catholic social tradition

-

“Windows of hope”—NDPEP’s reentry work pursues holistic thriving for returning citizens

-

ReSearching for the Common Good: Yunyan Zhao

-

Remembering Pope Francis—Institute faculty reflect on the pope’s influence on their work

-

Pursuing justice by getting proximate—Students explore themes of proximity, natality, and rootedness in spring break seminars