Pursuing justice by getting proximate

Students explore themes of proximity, natality, and rootedness in spring break seminars

April 16, 2025

Halle Keane stood on a downtown Los Angeles sidewalk with five of her Notre Dame classmates. They had just visited The Broad, a world-renowned art museum with million-dollar art pieces. Now, as they waited for their Uber, they stood just feet away from one of the nation’s largest tent cities, Skid Row.

The disparity between the two was stark.

This juxtaposition “frames the central dilemma of contemporary existence in a country as wealthy as the United States,” Keane later observed. “How can we stand on a street corner outside a world-famous museum, surrounded by luxury cars, while men, women, and children make their homes in tents on the other side of the street?”

At Notre Dame, Keane decided to add a minor in poverty studies at the Institute for Social Concerns to her major in economics in order to study wealth inequality. However, it wasn’t until her spring break trip for the Proximities seminar Arts of Dignity that she began to understand the why of her education: to pursue justice by getting proximate with those experiencing injustice.

“To solve the problems that surround us, we need to become active observers, able to recognize injustice,” she reflected. “For the six of us in Los Angeles, art was the medium through which we bore witness to injustice. Art facilitated dialogues that brought our attention back to poverty and systemic failures.”

Keane was one of two dozen Notre Dame undergraduates who spent their 2025 spring break on one of four trips for the inaugural Proximities seminars offered by the institute. From Los Angeles to Tucson to the Twin Cities to New Orleans, students visited locations and non-profits in the United States to briefly but intensely engage with a question of justice in a specific time and place.

Consistent with Notre Dame’s mission, the aim of the Proximities seminars is to create a sense of human solidarity and concern for the common good that will bear fruit as learning becomes service to justice. Guided by the institute’s justice education staff and postdocs, the students’ research was framed by three concepts: proximity, natality, and rootedness.

“It is essential, while you’re a student, to find ways to get proximate to those who are suffering, proximate to those who are excluded, proximate to the poor, proximate to those who are incarcerated, proximate to those who are hungry and in need.” –Bryan Stevenson

Aria Bossone is double majoring in American studies and peace studies with a minor in gender studies. She spent her spring break on a trip to Tucson, Arizona, to examine issues related to migration at the borderlands for the Proximities seminar Justice at the U.S.-Mexico Border.

Prior to the trip, the group watched the documentary Undeterred that told the story of residents of the small border town Arivaca protesting against the militarization of their town.

The next day, the students visited Arivaca.

“We talked to a man who works at the humanitarian aid office in Arivaca,” Bossone shared, “and he told us about a general solidarity that is felt in the community where migrants and migration as a whole are not viewed as a threat.”

The aid worker told the story of a man in the town whose political allegiances are associated with anti-immigration policies. But when this same man encountered a migrant walking through town, the man pointed him to where he could find water.

This story “highlights how complex these issues are,” Bossone stated. “Even for that person who has political beliefs that are associated with anti-immigration rhetoric, by just being proximate, he was much more understanding and humanizing of the migrants.”

“The miracle that saves the world . . . from its normal, ‘natural’ ruin is ultimately the fact of natality, in which the faculty of action is ontologically rooted. It is . . . the birth of new [people] and the new beginning, the action they are capable of by virtue of being born.” –Hannah Arendt

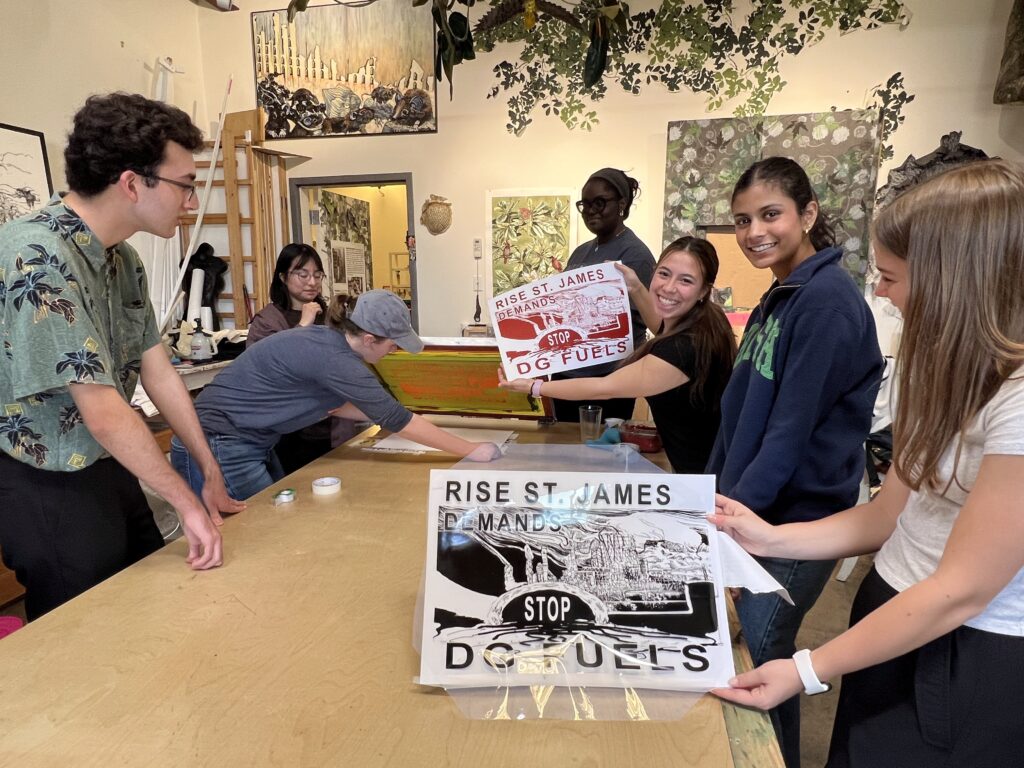

Natalia Gonzalez Giraldo and Ale Rodriguez joined four other students for the Proximities seminar Environmental Justice in Cancer Alley. They visited a region outside of New Orleans that has become known infamously as Cancer Alley due to the large numbers of petro-chemical companies located near residential communities there.

While there, they were able to sit in on an interview by MSNBC journalist and television host Alex Wagner with community members. In the interview, a sixty-year-old woman told how she is the oldest surviving member of her family, having lost family members to various kinds of cancer.

While it was difficult to comprehend the sheer scale of devastation from the petro-chemical companies, what stood out to Rodriguez was the determination of the community. They “know they’ve been poisoned, subjugated to the most life-threatening of pollutants, yet they remain in high spirits, remain adamant that if enough meaningful change is achieved, that they can begin anew,” he stated. “It was evident that in all the people we met, there lay a flame, a grit that strove them towards justice and never giving up.”

“It’s one thing to hear about environmental injustice,” Gonzalez Giraldo reflected. “It’s quite another to experience it and hear the testimonies of those impacted.” She was so moved by the witness of the community that she left with the determination “to figure out a way that we could help these residents scream for help.”

“A human being has roots by virtue of his [or her] real, active, and natural participation in the life of a community which preserves in living shape certain particular treasures of the past and certain particular expectations for the future.” –Simone Weil

A business analytics major, Marry De Austria joined the trip to the Twin Cities to research disparities in the healthcare system as part of the Whole Person Healthcare seminar. There she met Hannah, an employee of the Mino Bimaadiziwin Wellness Clinic (Mino-B). Hannah explained the historical trauma that Indigenous children face and how Mino-B seeks to heal it through programs like play therapy.

“Learning about the Indigenous community was eye-opening for me,” De Austria stated afterward. “Prior to this experience, I’ve had a one-dimensional view of what they’re facing and their issues because in classes we don’t learn a lot about them.”

One of the things she took away from her experience was the rootedness of the Indigenous community, especially after systematic attempts to uproot them. “I witnessed this unrootedness among Indigenous populations, whose forced displacement from their ancestral lands and the historical trauma inflicted by a government of broken promises still reverberate today,” she stated.

At the same time, the students witnessed the resilience of the Indigenous community as they visited Mino-B and the Native American Community Clinic, which works to address the health disparities within the urban Native American community of the Twin Cities. “Among Indigenous communities,” De Austria stated, “I witnessed people coming together to heal the wounds of historical trauma, supporting each other through a shared commitment to preserving their culture. Walking back and forth between Mino-B and the Native American Community Clinic, I felt the strength of a community determined to reclaim its identity and maintain its traditions.”

De Austria came away from her experience with a renewed “resolve to contribute to the betterment of the systems in society meant to protect and support those within.”

“Justice is the exercise of the supernatural love.” –Simone Weil

Hearing the students recount their experiences on the Proximities trips, Suzanne Shanahan, Leo and Arlene Hawk Executive Director of the Institute for Social Concerns, stated that it reminded her of a quote by Hannah Arendt that the point of education is to “decide whether we love the world enough to assume responsibility for it” and to try to “save it from ruin.”

“That’s what we do here in something like Proximities,” Shanahan continued. “It’s about developing that profound sense of social responsibility that we agree that the world is worth saving, and worth saving together. Getting proximate is one of the ways that we learned to take responsibility for the world and learn the tools by which we might save this world. And this is the profound experience you’ve all had over the past couple of months.”

She concluded with a charge to the students: “You are on your path to being able to see those things so many others don’t see, and in doing so save the world from ruin. At this moment, I can think of no more noble and profound task. So thank you again. Keep going.”

Related Stories

-

Social Concerns Summer Fellow returns to India for ongoing research

-

ReSearching for the Common Good: Solbee Kang

-

Bridging worlds through art—Kyla Walker joins institute as international poetry justice fellow

-

The power of encounter—RISE Hometown prepares incoming students for learning in service of justice at Notre Dame

-

The beauty of everyday democracy—Institute convenes scholars, practitioners, Luke Bretherton for democracy conference