I am often in conversation with people about some of the most weighty and challenging issues of our time—issues like anthropogenic climate change, environmental degradation, species extinctions, ongoing racism and income inequality, disease pandemics, the tearing of social fabrics, political polarization, and widely reported increases in personal stress, anxiety, depression, and despair. It is easy to become paralyzed by sorrow and fear in the face of the many forms of eco-socio-systems collapse. I suppose this is why these conversations almost always make their way to the question, “What gives you hope?” A compelling answer, presumably, will help us all feel better.

But assurances of hope can be seductive, and it is important not to assume that people want hope. Admonitions to “Be hopeful!,” though earnestly and sincerely meant, can be distracting and anesthetizing because, like a soporific, they lull people into an acceptance of the status quo. Suitably pacified, the task of hoping is reduced to waiting for the miracle that will in some hypothetical, perpetually deferred future make everything alright. Whether it is religious leaders who have told their followers to accept their suffering and endure every hardship because God will, in the end, somehow, make everything right, or business tycoons and technology gurus who tell their followers that there will always be a technological fix that will get people (at least those who can afford it) out of whatever troubles they find themselves in, people have not been well served by these expressions of “faith” that often mollify and render them spectators of their own lives. This is why the indigenous philosopher Kyle Whyte instructs us to be cautious around the (often comfortable and well-satisfied) purveyors of hope. Their calls to hopefulness can generate what he calls the “ultimate bystander effect” that excuses people from the hard work of correcting the injustices that create hopelessness in the first place.2

It is also important to be clear that hope and optimism are not the same thing. One can even say that optimism works against hope because it does not sufficiently acknowledge or protest against the injustices that currently degrade and destroy life. As the literary and cultural critic Terry Eagleton has persuasively argued, optimists tend to be rather conservative in their outlook and all too accepting of the status quo. They put their trust in “the essential soundness of the present,” and do not have the creativity or energy to work for a more praiseworthy future.1 There is a fundamental blindness, even dishonesty, in the cheery optimist’s outlook because it does not properly name or adequately account for the injustices of the past or the present that are causing people to despair in the first place.2

And yet even for those of us who endorse a clear-eyed embrace of hope, I am no longer sure that “What gives you hope?” is the right question to be asking. The framing can make hope seem like a thing we can pick up along life’s way. Some people have it. Some people don’t. The key is to find it, hold onto it tightly, and (ideally) pass it along to those who are without hope. The temptation, then, is to think that hope works like a shield or, less combatively, a security blanket that protects people from the many troubles of this world. I understand the temptation. I too want assurances that everything, somehow, no matter what, is going to be alright. My concern with this framing, however, is that it casts hope as something that people simply acquire, like a vaccine that renders people immune to this world’s troubles.

But what if hope isn’t really, or at least not fundamentally, a thing to possess? What if hope is, instead, a self-involving way of being that is inspired and animated by an affirmation of the goodness of this life, or a practiced way of life rooted in the conviction that this life is worth cherishing, defending, and celebrating? I have found that creative and energizing ways of thinking open up when people think of hope less as a noun and more as a verb.

I recognize that this is an uncommon way of speaking, which is why I now shift the question from “What gives you hope?” to “What do you love?” I make the shift to love because conversation and reading have taught me that people who live in hope do not seek to shield themselves from the pains and problems of this life. They engage the trouble, and thereby demonstrate that hope grows, and its meaning is more fully discovered, in the action of working for a better world. The most important matter is not that people have a fully worked out picture of what a better world looks like, or have a clear sense of the exact form their action should take. It is, with humility, to act on the conviction that your world needs you and is calling you to contribute in some way. To ask people about what they love also has the merit of opening a space for two further important questions that bear directly on living a hopeful life: “What inspires or activates your love?” and “What are the social and economic conditions that optimize a loving way of being?” Apart from having someone to love and places and things to cherish, and apart from feeling the love of others, it is hard to see how hope has a future.

The most succinct way I know to express my core convictions is to say that hope germinates wherever and whenever love goes to work. It grows as love takes root in one’s world and in one’s life. It flowers and fruits when people feel the power of love nurturing and healing the communities through which they live. Hope and love are inseparable because a hopeful way of being depends on the experience of mutual nurture and the feeling that one’s life matters and is worthy of protecting and celebrating. Hope withers in contexts of anonymity, abandonment, and abuse.

The stories of the people who inspire hope in others teach us that hope and action are inseparable, and that they are held together by a yearning for a more beautiful and just world. Greta Thunberg is instructive in this regard. Thunberg says that it was at age 8 that she first heard about climate change and what it meant for the life of this planet. It put her into a deep depression. She stopped talking. She didn’t eat. She couldn’t understand why politicians, educators, and business leaders were not doing everything they could to address what, in her mind, was the most important crisis humanity has ever faced. One day, years later, she followed the advice she now regularly gives to others: “Act. Do something!” On August 20, 2018 she went to the Swedish parliament buildings, sat down with a sign, and initiated the first “school strike for climate.” Before she knew it, and in ways that she still does not fully understand, her action went viral on social media. Others sat down with her. Journalists came to interview her. School strikes began in other Swedish cities and then in other countries. Two months later, tens of thousands of students from around the world were joining her by striking and marching down their city streets. A little over one year later, an estimated 4 million students and adults in 170 countries participated in a Global Climate Strike.

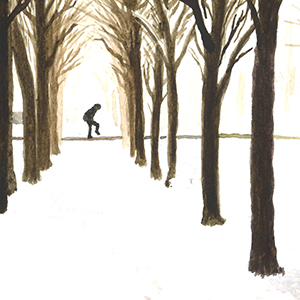

Will these actions change the world? No one knows. There are no guarantees that the world hopeful people desire will come about, because they know that existing troubles will likely persist and new ones emerge. They cannot be certain that the world they desire is even the best one, since human knowing is always mixed with fallibility and ignorance. This is why it is important to remember that hopeful action is an inherently risky endeavor that is subject to frustration, correction, and disappointment. Our loves can be malformed and misdirected. The crucial thing, as Rebecca Solnit has argued in her insightful book Hope in the Dark, is that people not think hope is like a lottery ticket. Hope is a power that propels people off the couch and out the door. “Hope calls for action; action is impossible without hope . . . To hope is to give yourself to the future, and that commitment to the future makes the present inhabitable.”3 Hope, we can say, is born in spaces of vulnerability as people open themselves to, and allow themselves to be moved by, whatever trouble and whatever goodness and beauty are happening around them. It grows as they commit themselves to sharing and extending this goodness and beauty with others, and by learning how best to care for each other while in the midst of the trouble.

“Hope lives in the means, not the ends,” says Wendell Berry.4 His point is important to emphasize for two reasons: first, we don’t know enough to comprehend all that is happening in the present, let alone the future, which is why we should not put too much confidence in making predictions about outcomes; and second, undue focus on outcomes can distract us from discerning and doing the good we need to do in response to current damage and loss. The cardinal mistake of both pessimists and optimists is that they assume too much certainty. Hope moves within the spaces of uncertainty, and searches for the goodness that is believed to be reality’s heart. To love and to hope is to trust that it is worthwhile to seek and nurture the good despite the damage and ruination we see. It is to assume that change for the better is rarely straightforward and quick, but often slow and unexpected. Hopeful people do not expect to solve it all. Their aim is more modest, because they understand that this world and its life are more complex and mysterious than anyone can comprehend. At the most fundamental level, what moves them is a love for this life.

The biblical sage Quoheleth once remarked that “whoever is joined with all the living has hope” (Ecclesiastes 9:4). Learning to join with others in a shared, mutually nurturing life isn’t easy. This is why our most crucial task may yet be to help each other live attentively and sympathetically with each other and in ways that affirm, heal, and reconcile life. This doesn’t mean that the future doesn’t matter, or that we should dismiss scientific forecasts about matters such as sea level rise and cataclysmic weather events. Hope’s focus, instead, is on inspiring the commitment and developing the practices that position people to live now in ways that nurture and heal life. We do not owe people of the future an accurate prediction of what their life will be. What we owe them is a commitment to do now the good work that will lessen the prospect of a future nightmare. Doing good work, we also cultivate the conditions in which a decent life can grow, and our lives themselves are signs of hope.

Notes

- In Hope Without Optimism (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2015), Terry Eagleton says “Optimists are conservatives because their faith in a benign future is rooted in their trust in the essential soundness of the present. Indeed, optimism is a typical component of ruling-class ideologies . . . Only if you view your situation as critical do you recognize the need to transform it. Dissatisfaction can be a goad to reform. . . . True hope is needed most when the situation is at its starkest, a state of extremity that optimism is generally loath to acknowledge” (4–5).

- In a conversation with Britt Wray, Kyle Whyte contrasts the hope that is committed to action and the hope that waits for a miracle. The latter is often disingenuous and dangerous because the political and economic structures that perpetuate current forms of privilege also make a miracle even more improbable. See “How Can You Hope When You Are Coming Out Of A Dystopia?” (gendread.substack.com/p/how-can-you-hope-when-youre-coming).

- Rebecca Solnit. Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2016),

- Wendell Berry. “Discipline and Hope,” in A Continuous Harmony: Essays Cultural and Agricultural (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972), 131.