From the Editor

Welcome

Suzanne Shanahan, Editor

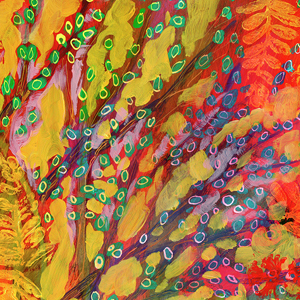

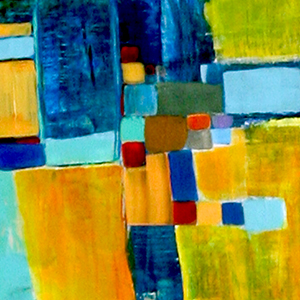

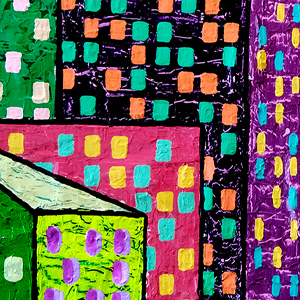

Artwork: “July is Bursting” by Christopher Noxon © 2023

I spent most of June in Dublin. My first academic job was in Ireland—almost 30 years ago in the Sociology faculty at University College Dublin. I stayed only two years. But my family has since then visited Dublin at least a couple of times each year. It is a second home of sorts. It feels wonderfully familiar.

This is where I first read the essays that appear in this issue of the Virtues & Vocations magazine on generosity. They helped me understand something that has long alluded me.

A big part of that familiarity that we love in coming to Dublin is seeing people we know: friends, colleagues, business owners. Some of those familiar faces are also part of a significant homeless population who have been unhoused for these same three decades. As a family we know their names, we know their stories, we know where they are perched in the city. We expect to see them in certain spots around town. My husband, Bill, is what the rest of us would consider “oddly close” to these individuals. Bill always takes time to talk and catch up, always provides some money—and often substantial sums. He has on occasion provided things like the raincoat off his back or shoes off his feet. People rarely ever ask, but Bill gives nonetheless. They share more than familiarity, but perhaps less than friendship.

Bill’s behavior no longer surprises his family, even if the impetus for it is still not fully understood. We marvel at his consistency. We are perplexed by the extent he’ll go to always make sure he has some cash on hand to offer. We also find it funny because he is otherwise quite frugal; some would even say cheap. Bill struggles himself to explain it. Is it a form of social responsibility? It is guilt around his own privilege? It is the fact he was born in Ireland? Is it about his faith? He demonstrates the same generosity with the unhoused population in South Bend. Bill is, then, consistent. But still Bill has no particular commitment to, or even profound interest in, the challenge of homelessness, nor does he entertain more systemic interventions. In some sense it is as if their housing status really doesn’t matter. This is just what Bill does.

This context is how I come to my thinking about the virtue of generosity and this next issue of Virtues & Vocations: Higher Education for Human Flourishing. For many years I did not consider my husband’s behavior as a form of generosity, but these essays helped me understand his instinctual empathy and compassion that doesn’t differentiate. He does not think the funds actually change anything for the individual beyond the moment of the giving. It is the same way of being that prompted him to invite the cashier he just met at Target to our daughter’s birthday party simply because he thought they’d enjoy it. It is not theorized, it is not part of a larger politics, it is untied to his Catholic faith. It is not even some personal, well-honed retort to the effective altruism against which he often rails. It is emotive and embodied. Bill’s generosity is perhaps best described in the language Jack Bell eloquently employs when he invokes Artistole: “Aristotle wrote that the generous person knows what to give at the right time to the right people. When the right opportunity comes, he parts with what he has, regardless of whether he knows or loves the recipient.”

While these essays all share elements of what I see in Bill’s particular behavior, their variety and distinctiveness also illuminate the breadth and depth of what we mean when we invoke the term generosity. The engineers, farmers, historians, philosophers, physicians, and theologians here clearly bring different scholarly traditions to the question of generosity, but they are each also distinctively shaped by personal experiences of encounter and community. We see explorations of generosity focused more directly on the student experience in the essays by Joshua Brake and Sarah Schnitker, and a look at broad global challenges such as hunger and inequality from the essays by Jack Bell and Dirk Philipsen. Melissa Fitzpatrick reminds us of the challenges of living radical love without self-love and care. Abraham Nussbaum helps us see that how we are generous matters as much as the generosity itself.

In the interlude we offer an interview about generosity with Fr. Greg Boyle of Homeboy Industries, who reflects on more than 30 years of transformative work in community, which has been based on a notion of kinship and radical love for anyone—whomever they are, wherever they are from, whatever they have done. We also share an essay from Associate Professor of Studio Art at Notre Dame, Fr. Martin Lam Nguyen. Fr. Martin’s work is about the art of seeing: physically, visually, and existentially, as a discipline and practice. In his essay, he reflects on the freedom unconditional love can afford. He reminds us that a life of generosity is the opposite of a life of calculation. Fr. Martin works with the incarcerated, teaching art to men at the Westville Correctional Facility in Indiana, enabling them too to be free.

In this issue, we chose art with an eye to abundance, reflecting a way of seeing and being that propels generosity. The art reminds us that generosity takes many shapes, but is inextricably linked to flourishing.

I hope this issue prompts you to reflect on the generous people in your own life, and provides as much insight and wonder as it offered me.

–Suzanne Shanahan

Suzanne Shanahan is the Leo and Arlene Hawk Executive Director, Institute for Social Concerns, University of Notre Dame.

Fall 2024

Part I: Abundant Virtue

Laurie L. Patton

Sarah A. Schnitker

Patricia Snell Herzog

Melissa Fitzpatrick

Dirk Philipsen

Interlude: Generous Eyes, Radical Love

Fr. Martin Lam Nguyen, CSC

Part II: Abundant Vocation

MORE